Harvesting the Wind and the Past

When Ibrahim Bin Mohammed Al Midfa identified the site of his home in Sharjah back in the 1920s, effective ventilation was a prime consideration.

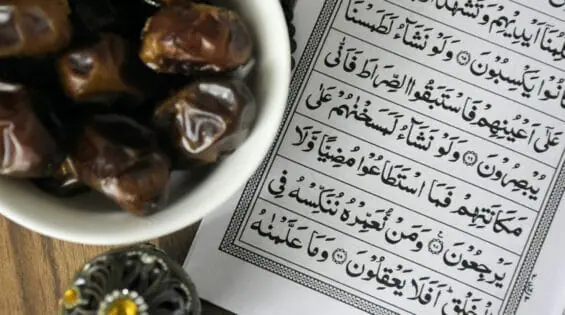

A renaissance man of heady renown, Ibrahim – the scion of a trading family that owed its wealth to the lucrative trade in dates, rice, spices and perfume – was one of the most active hosts in the region.

As a publisher, he had just launched The Oman, the first newspaper in the history of the UAE. His intense passion for weighty subjects like calligraphy, literature and poetry, meanwhile, drew the cream of Sharjah’s intellectual community to his majlis (the meeting room in Arab households) on an almost daily basis.

So far, so convivial, but Ibrahim – like other Gulf homebuilders of the era – also had to contend with the broiling heat of the Arabian Peninsula.

The elephant door is original to the home of Ibrahim Al Midfa. The year, 1944 or 1363 in Arabic calendar is noted in Arabic above the door. Today, these beautifully wrought doors open onto the resort’s library and museum.

The closest equivalent to the traditional majlis may have been the salons of Paris: the gatherings that played an integral role in the cultural and philosophical development of France.

But, as even the liveliest Arab minds will admit, it’s far easier to explore the realms of art, literature, music and current events in temperate Europe than it is in the hothouse of a Gulf summer, when gentle breezes floating in from the sea struggle against high heat.

Barjeels as Agents of Change

The solution lay in an architectural marvel dating back to ancient Egypt. For millennia, windtowers, known in Farsi as badgirr and in Arabic as barjil or barjeel, have provided natural ventilation by harnessing the prevailing wind and funnelling it down the tower into the heart of the building to maintain airflow. While forcing the cool air down into the home, the ingenious design of the towers allows hot air to rise out the top of them.

The design of a barjeel, or windtower, does not conform to any specific geometry but works to catch the prevailing wind from on high. When there’s no wind, less dense hot air flows up and out.

The design of a barjeel, or windtower, does not conform to any specific geometry but works to catch the prevailing wind from on high. When there’s no wind, less dense hot air flows up and out.

By incorporating this feature in his abode Ibrahim ensured that the daily discourse in his majlis was conducted in comfort. Indeed, he went further than most builders by constructing a circular windtower with decorative tiles imported from India.

In its time, due to the prominence of its owner, Ibrahim’s home was as important a centre in the community as a school or a mosque. In fact, his wind tower looks a lot like the minaret of a mosque and stands today as the only example of its kind in the Emirates. It is now an integral feature of Al Bait Sharjah, a luxurious heritage resort that is preparing to open its doors later this year.

Not only did the barjeel help enhance the social standing of engaging figures like Ibrahim, its widespread adoption in homes transformed society in the UAE from its nomadic, tribal origins to one with stronger, physically tangible, anchors. Just as air conditioning has changed the face of the modern UAE and the lives of those who live in it, so too did the introduction of barjeels to Sharjah and other emirates in the early part of the 19th Century.

The towers had long been a feature of homes in harsh, hot climates by the time Persian immigrants introduced them to the emirates that lined the southwestern shore of the Gulf.

Setting Down Roots With Towers

The first examples of wind tower construction date from 3100BC. Later, their cooling possibilities were harnessed throughout Persia and in parts of Pakistan and Afghanistan. The introduction of barjeels in the UAE (then known as the Trucial States) had what could only be described though as a revolutionary impact.

Before then, the unforgiving desert environment led to the emergence of nomadic groups who subsisted due to a variety of economic activities including animal husbandry, agriculture and hunting. Life was less transient on the coastal areas where ports such as Dubai and Sharjah were nurtured by the thriving pearling industry on the Persian Gulf as well as the growth in international trade.

And it was in these population centres, along the generous creeks that wind their way inland from the Gulf, that the moneyed class attached cooling structures to their urban mansions. By doing so, they helped establish a sense of permanence to these settlements and sowed the seeds of a sophisticated modern Arab state.

The first windtower homes in the UAE were constructed using palm fronds. Later, though, builders turned to sea stone and coral from the sea creeks, which was tacked in a bricking fashion, set with a mixture of mud, sand, gypsum and limestone and then covered with a layer of sand, mud and rock for added insulation and protection.

With the barjeel ball now well and truly rolling, the momentum of construction was irresistible. During the first half of the 20th century, a high spec new home in the UAE was incomplete without a wind tower.

While families of more humble bearing had to content themselves with simple structures, the Emirati elite built their barjeels ever higher and more ornate, to both enhance their status and to trap even more of the precious prevailing breeze.

Sadly, the glory days of barjeels have long since gone. Cities such as Sharjah, Abu Dhabi and Dubai have developed beyond all recognition and air-conditioning is now undisputed king when it comes to ventilating the homes of the UAE.

Barjeels have been fixtures in Arab cultures for several thousand years. (Photo credit: Sharjah Tourism Authority)

Barjeels have been fixtures in Arab cultures for several thousand years. (Photo credit: Sharjah Tourism Authority)

Perhaps more tragic is the fact that many original wind tower homes have been demolished in the breakneck rush to develop, leaving a mere handful of examples in heritage areas such as Al Bastakiya and Al Shindagha in Dubai and, in Sharjah, the Heart of Sharjah: the largest historical preservation and restoration project in the region, of which the new Al Bait Sharjah resort will act as a focal point.

A Stamp of Authenticity

Energy consumption solely for air-conditioning is one of the Middle East’s most pressing looming headaches. As a means of addressing this, engineers are now looking at ways of harnessing aspects of barjeel architecture as a way of providing zero-energy cooling for contemporary buildings.

While the fundamentals of barjeel architecture may still have a role to play in the modern era, historians are doubtful of a widespread comeback. They can’t see that barjeels will be used in the future as anything more than decoration or as an educational heritage feature, however effective they were in the past.

Be that as it may, Ibrahim’s majestic round barjeel is set to once more become a beacon for lively social interaction as part of Al Bait Sharjah.

The incorporation of the unique wind tower gives the new heritage resort an emphatic stamp of authenticity and individuality. Indeed, the presence in the building of the only remaining example of a cylindrically-shaped wind tower in the UAE is sure to serve as a major drawcard for those who appreciate history.

The tower that cooled Ibrahim Al Midfa, his family and their friends are poised to inspire travellers to the heart of Sharjah.

The tower that cooled Ibrahim Al Midfa, his family and their friends are poised to inspire travellers to the heart of Sharjah.

And with plush suites and contemporary trimmings such as spa, swimming pool, cigar lounge and gourmet restaurants, the resort showcases Arabic hospitality on an even more spectacular scale than in Ibrahim’s heyday.

Nevertheless, guests should expect to experience the spirit of old Sharjah, in the view of Al Bait Sharjah General Manager Patrick Moukarzel.

“Al Bait means home in Arabic,” he says.

“Although there’s plenty of luxury, we want to maintain a sense of humbleness and intelligence. There’s a library where guests can browse over 400 books about the culture of the UAE. There are also many majlis. Staying here is like visiting someone in their home.”

The rotating door that separates the museum from the library may, at the same time, enable a bit of time travel.

It’s an ethos you suspect that the young firebrand Ibrahim and his learned friends – cooled and intellectually rejuvenated by the breeze flowing down through the barjeel – would have approved.

Text by Duncan Forgan for GHM Journeys and photographs courtesy of Al Bait Sharjah & SCTDA (Sharjah Tourism Authority).

Featured image: Courtyards, like this stunning new space at the Al Bait Sharjah, were part and parcel of heat-management strategies in traditional Arab architecture.

First published on 17 November 2018.