The First of Four Chambers at the Heart of Sharjah

Dubai captured the world’s attention earlier this year when the world’s tallest hotel opened in a structure 356 metres high. That 77-storey tower claimed the title from a neighbouring hotel, which now has to play second fiddle at 355 metres. The Guinness Book of World Records calls this new building the tallest hotel building in the world, but it’s not the highest, for a Hong Kong hotel occupies the 102nd to the 118th floors of a skyscraper.

Standing in Dubai, where six of the world’s tallest 10 buildings shoot for the stars, you get vertigo just thinking about the prospect of a good night’s sleep. But there are antidotes in development, and one of them is taking root 25 kilometres to the northeast in Sharjah, where the Al Bait Sharjah, UAE is preparing to open its doors — at ground level — later this year.

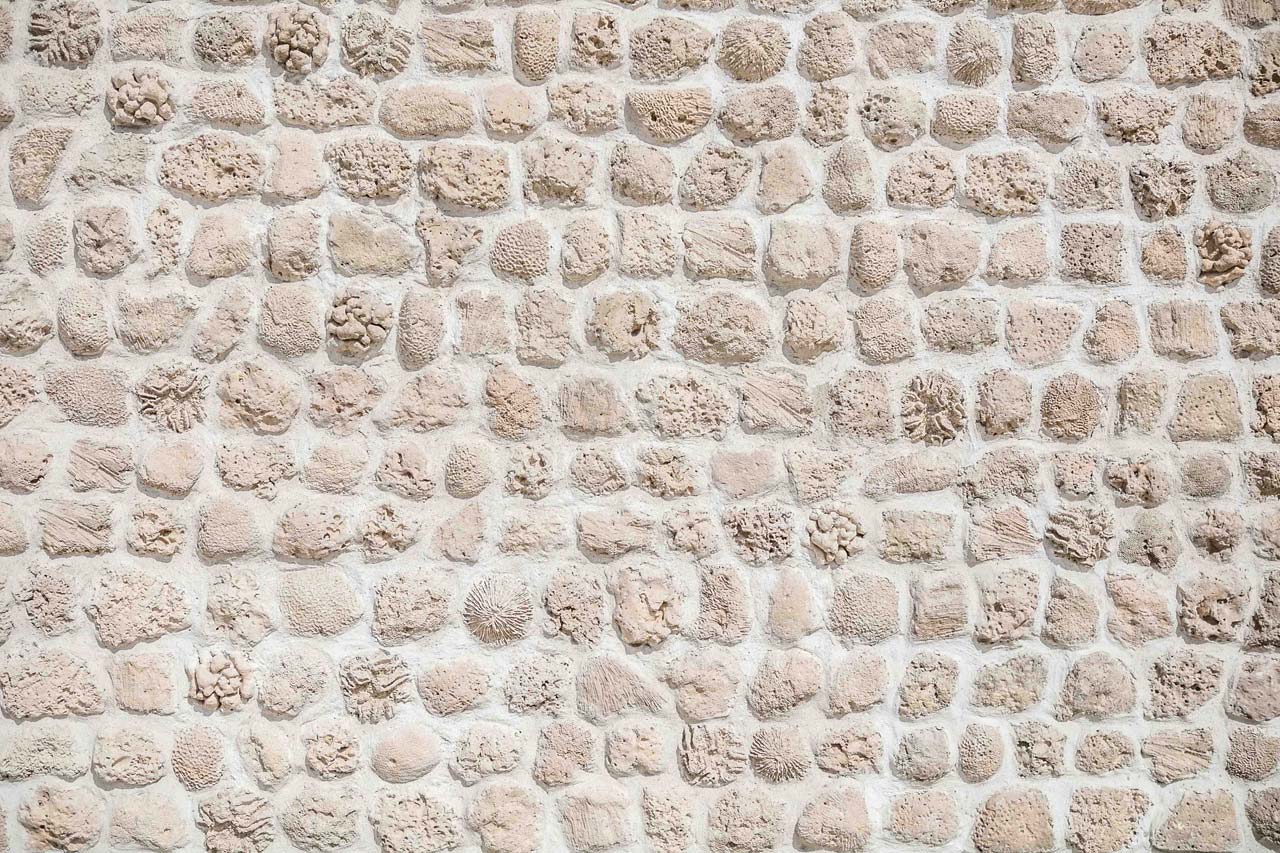

There are four chambers to the heart of the resort, each one a relic of days gone by when the world wasn’t so flat and the homes people built for themselves owed everything to local style and taste. In 1927, a young man named Ibrahim Bin Mohammed Al Midfa mined the environs for coral stone and gypsum, and imported teak, to build a home for himself. His brothers started work on three additional homes nearby, each of them standing on the storied foundation of their family’s heritage.

The Al Midfa family traced its origins to Oman, and its wealth to sailing ships that brought in dates from Al Misra, rice from India and perfumes from Africa. They supported pearl divers in the seas around Arabia, and reaped a harvest that established the family in Sharjah, where Ibrahim was born in 1909. He studied the Quran as a boy, of course, but calligraphy, too. He read deeply from anything he could get his hands on — newspapers, magazines, books — and by the time he turned 18, he launched his own newspaper. His family had been in Sharjah since 1660, but for the name of his paper he referenced the Al Midfa family roots, calling his new periodical the Oman Newspaper.

![]() Mr. Al Midfa encouraged fathers to bring their children to the majlis so the younger male generation could learn about traditions and form a bond between the generations.

Mr. Al Midfa encouraged fathers to bring their children to the majlis so the younger male generation could learn about traditions and form a bond between the generations.

Oman wasn’t run off a press, but was the product of handwriting. Ibrahim wrote out a new edition every other week, and only produced a half-dozen issues, which were passed by hand from reader to reader and posted in the nearby souq. The Oman was notable for its sarcasm, and for the way it decried foreign influences in the Emirates.

At the same time he was establishing himself as a man of letters, Ibrahim was settling into his new house. Part of that house — its majlis, its verandah and courtyard — now form The Café of the incipient Al Bait Sharjah.

The majlis, according to Sharjah educator Fatima Salim Al Shuweihi, was the gathering place for guests who called on the Al Midfas. “If my friends come calling, and we’re planning some discussion, we wouldn’t take them to the living room, but to the majlis. The French would call this a salon.”

Building stones are bonded together with jus, a lime-based mortar also used for plastering and interior decoration.

Building stones are bonded together with jus, a lime-based mortar also used for plastering and interior decoration.

Owing to Ibrahim’s prominence in the community, his majlis developed into a complement of sorts to the mosque and the school. The community’s intelligentsia gathered here to discuss everything from poetry to politics in a space that was as august as their ambitions. Indeed, like a beacon to the lofty talk taking place below, Ibrahim built a wind tower on top of his majlis that looks a lot like the minaret of a mosque and stands today as the only example of its kind in the Emirates.

Outside the majlis, a verandah stretched the length of a building that features four great, serrated archways and columns on its exterior side. Mangrove poles supported the roof, and mats of palm leaves insulated the space below against the brunt of the sun. Inside the majlis, wind scoops in false walls helped ventilate the hall. Beyond the verandah there is a capacious courtyard where a tree shades some of the space.

Construction, using the original materials, was undertaken by the Directorate of Heritage and took around 4 years to complete.

Construction, using the original materials, was undertaken by the Directorate of Heritage and took around 4 years to complete.

When daytime temperatures soared in summer, and the curtain of night brought little relief, the Al Midfa family sought relief in this courtyard, said Fatima’s mother, who grew up in this seaside enclave.

“She said the courtyard back in the day was multi-purpose,” said Fatima. “And quite often at night during the hottest months, members of the Al Midfa family would carry their mattresses into the courtyard around the tree for better sleep. It was a simple life.”

A dallah, or Arabic coffee pot, will once again anchor social activities in the one-time Majlis Al Midfa.

A dallah, or Arabic coffee pot, will once again anchor social activities in the one-time Majlis Al Midfa.

The Al Midfa family moved out of its home in the 1970s, preferring contemporary accommodation that would afford them electricity and running water indoors. Ibrahim’s old home slipped into disrepair until the house was revived by renovation and opened to the public in 1996.

That tree is still growing in the courtyard, and is shaping up as the anchor to a collection of outdoor tables in the resort’s new café. It’ll be a place for tea, for coffee, for local sweets or European pastries and a place, perhaps, where discussion will flow again.

Text by Jim Sullivan for GHM Journeys

Featured image: Coral was widely used as building material in old Sharjah.

First published on 4 May 2018.